Wednesday, 5 November 2014

Write Now!

A short and salty post: are you a writer in Edinburgh (or near by and willing to travel in)? If so check out the art work of Christopher Orr.

The Talbot Rice Gallery in Edinburgh is looking for writers who wish to respond to Orr's paintings. For more information drop me a quick email at russ_jones2k@hotmail.com Now, away with you, orr else!

Russell Jones

Friday, 24 October 2014

Two Plugs are Better than One!

Right, you lily livered scallywags, what have you asked Santa Claus for? Go on, tell me, I won't let him in on the secret that you've been incredibly naughty. And at your age!

Well there's no chance you're getting those things, not now. Instead you ought to buy these two books. Several copies of each, some for yourself, some for your loved ones, some for your enemies. They feature a hoard of fine poems from upstanding people unlike yourself.

Be the First to Like This: New Scottish Poetry

Vagabond Press

Edited by Colin Waters

This collection is awash with fine poems from almost 40 of Scotland's versifiers. It includes work from Claire Askew, Colin McGuire, Michael Pederson, Aiko Harman, William Letford...the list goes on. 3 poems per poet, giving a nice feel for what they're all about. I've also a few ditties in there.

Double Bill

Red Squirrel Press

Edited by Andy Jackson

This collection takes inspiration from popular culture such as music, TV and the BIG screen. It makes strange links between its sources, comparing Judge Judy with Judge Dredd, among others. MANY poems and poets including Ryan Van Winkle, JL Williams, Sally Evans, Andy Jackson, WN Herbert, Chrissy Williams...the list never ends.

Buy them NOW. Or I'm telling Santa and he won't be happy. Ho. Ho. Ho.

Russell Jones

Monday, 13 October 2014

Poet Profile: Paul Farley

Paul

Farley

The

background.

Paul

Farley grew up in Liverpool and studied painting in Chelsea. He’s won (or been

shortlisted) for a sack full of prizes including the TS Eliot award. As well as

publishing poetry on the page he’s been a big name on the radio waves, broadcasting

poetry and drama. Check out a fuller list here.

Why this

poet?

Paul was

my poetry tutor back in the days when I was a teeny weeny undergrad at

Lancaster University. At the time I don’t think I realised just how great a poet

he was. We’d go to the pub, he’d recite dirty limericks and tell us horrifying

and hilarious stories. His poetry has an awesome musical quality to it which

comes through on the page, but hearing it is even better. His book titles

remind me of Stereophonics songs for some reason, which is no bad thing: “The

Boy from the Chemist is Here to See You” and “Tramp in Flames” for example. His

poetic voice is unique and full of charisma, and his poems expertly capture a

sense of time and place, tackling difficult issues with a combination of subtlety

and flamboyance.

A poem

extract

(from “Tramp

in Flames”, in the collection “Tramp in Flames” Picador, 2006)

Some

similes act like heat shields for re-entry

to reality:

a tramp in flames on the floor.

We can say

Flame on! to invoke the Human Torch

From the

Fantastic Four. We can switch to art

[...]

my uncle

said the burning bodies rose

like Draculas

from their boxes.

But

his layers

burn brightly

and the salts locked in his hems

give off

the colours of a Roman candle

[...]

in the

middle of the city he was born in,

and the

bin bags melt and fuse him to the pavement

and a pool

forms like the way he wet himself

sat on the

school floor forty years before,

and then

the hand goes up. The hand goes up.

A reading

That same

old issue, of course – this is just an extract, albeit about half the poem.

Farley is

a master of “turning the line”, which is to say that the lines shift meaning depending on how you read them. Any line in his poems

stands well on its own, but then look what happens when you read the line

before it, or the one after: it changes subtly but significantly. Let’s look at

an example...

Some

similes act like heat shields for re-entry

to reality:

a tramp in flames on the floor.

We can say

Flame on! to invoke the Human Torch

Taken on

its own “to reality: a tramp in flames on the floor.” hits hard. The narrator instructs us of the reality of a man burning in the streets. It’s almost

dismissive; this person is “a tramp”, somehow not a human or fully formed character. We learn nothing

of him until the end, only his title of “tramp”.

Now attach

the first line to it ("Some similes act like heat shields for re-entry to reality:

a tramp in flames on the floor.") Suddenly we’re in a kind of literary outer

space in which similes protect us from the reality of a burning man. It’s

completely true, think about how we talk about death. We rarely say, “I’m sorry

x person is dead.” We say “he’s passed on”, “he’s no longer with us”. It’s a

simile for death but we use it to soften the blow, as a heat shield against the

fire of reality, which is too hot to handle.

And then

join the last line to the second (to reality: a tramp in flames on the floor. We

can say Flame on! to invoke the Human

Torch). It’s a cruel joke, isn’t it? The narrator suddenly moves away from reality, perhaps

because they can’t take the image, and they turn it into a bit of a joke by

comparing the man to the Human Torch from Marvel comic books.

What is it

saying then? We placate ourselves and ignore the cruel reality of what is

happening. Later the poem refers to “the city he was born in” and the tramp’s life at school when he’s (we assume) asking for help: “and then the hand goes

up. The hand goes up.” Even here,

Farley’s challenging how we read the line. “The hand goes up” in class to ask

for help, and he stresses it again (The

hand goes up.) to show the LACK of help. Is this poem really about someone

burning? Well, it could have happened or simply be imagined. But it seems to be suggesting that we, as

individuals and a society, find reasons to ignore social inequalities and those

who need help, not only when they’re adults but also throughout their lives. Choosing ignorance is what causes the problem, the burning.

This is

only my take on the poem, of course, but I strongly encourage anyone to take a

look at this poem for themselves. “Turning the line” (I’ve just made that up by

the way, I’m sure it has a proper name) is something Farley is a master of, but

his poems have such a powerful voice that frequently capture time and location

so brilliantly. Reading him is a masterclass in impactful and thoughtful verse.

Go read...

The Boy From the Chemist is Here to See You (Picador, 1998).

The Ice Age (Picador, 2002).

Tramp in Flames (Picador, 2006).

The Dark Film (Picador, 2012). - this one was shortlisted for the TS Eliot prize

Listen to Farley’s poem, “Treacle”, here.

Wednesday, 10 September 2014

A filthy sonnet

There ain't much poetry on this poetry blog, so here's a sonnet from my upcoming collection "Our Terraced Hum" (part of a 5 poet anthology called "Caboodle", from Prole Books, 2014). This poem will also feature in my first full collection, "The Green Dress Whose Girl is Sleeping" (Freight Books, 2015).

Get messy.

Basement

Beneath the Corner Shop

He’s made himself the castle of his dreams:

the landfill lord, a tin can Midas

moated by nine months of debris. He beams

in the grit of his homemade fortress

because nothing outside can finger through

the pizza-box walls cracked by arrow loops,

his cardboard curtain. The hullaballoo

of reality is cut by his coup

d'état, cartons stacked, wrappers tacked, intact

in the order of chaos. Passersby

gleer in, hands fanned over their eyes, retract,

shake their faces at the teem of house flies.

They mark him the idol of their own disgust

when in public but, privately, they lust.

He’s made himself the castle of his dreams:

the landfill lord, a tin can Midas

moated by nine months of debris. He beams

in the grit of his homemade fortress

because nothing outside can finger through

the pizza-box walls cracked by arrow loops,

his cardboard curtain. The hullaballoo

of reality is cut by his coup

d'état, cartons stacked, wrappers tacked, intact

in the order of chaos. Passersby

gleer in, hands fanned over their eyes, retract,

shake their faces at the teem of house flies.

They mark him the idol of their own disgust

when in public but, privately, they lust.

Russell Jones

Poet Profiles 2: Jo Shapcott

Jo Shapcott

The background.

Jo Shapcott is from

London but studied in Dublin. She teaches Creative Writing at Royal Holloway. Her poetry has won some big awards including the Costa Prize and the Forward Prize. Aside from poetry she has also studied science with the Open University. Her

collection “Of Mutability” (2011) explores her experiences of having breast

cancer.

Why this poet?

She’s one that sticks in my head, like a piece of tasty

gristle between my gnashers. If nothing else, her turns of phrase can make me tingle and gurn. Her first collection, for example, she titled: “Electroplating

the Baby”. Frankly I don’t think you can beat that. Her poetry is diverse too,

from knitting to pissing, cancer to chemistry. She’s interested in everyday

life but her poems also talk about bigger issues such as gender and identity.

A poem extract

(from “Of Mutability” – read the full poem here)

Too many of the best cells in my body

are itching, feeling jagged, turning raw

in this spring chill. It’s two thousand and four

and I don’t know a soul who doesn’t feel small

among the numbers. Razor small.

[...]

Look up to catch eclipses, gold leaf, comets,

angels, chandeliers, out of the corner of your eye,

join them if you like, learn astrophysics, or

learn folksong, human sacrifice, mortality

A reading

I hate having to paste bits of poems, it really ruins the

overall impact. However, we’ll have to cope.

What I love about this poem is how personal it is, and yet

it blasts outwards to take in the ‘grand scheme of things’. Shapcott’s choice of words in the first stanza

is brutal: “itching”, “jagged”, “raw” and these words would feel tired if it

weren’t for the fact that she’s not talking about flesh as we might expect it,

she’s talking about her “best cells”. Of course the fact that these are the “best”

ones means that what’s unmentioned (the “worse cells”) is all the more potent. She’s

breaking apart. We’re next to her, listening to her talk about her body’s

rebellion, and we know this could happen to us too.

And then BOOM, here come the comets and angels. We’re told

we can join them, we can learn “astrophysics or folksong”. Is this hope? It’s

those things we imagine, those things we don’t quite know, “in the corner of

your eye” that open up opportunities. That dissolving body becomes secondary to

the possibilities of the mind, but it was the learning of her mortality, and

our own, that brings about such vast change and inspiration. It’s as though she’s

saying 'once you let go, you’re free to be something else.' She’s prodded life in the eye and she seems to come out victorious, or at least transformed.

I think this poem teaches us something: every experience,

even very challenging, even life threatening, can change the way we think about

the world and our place in it.

Go read...

Of Mutability (winner of the Costa Book of the Year Award)

Her Book: Poems 1988-1998.

Electroplating the Baby (winner of the Commonwealth Poetry

Prize for best first collection) - I think you have to get this second hand now, or read parts of it in her collected poems

Emergency Kit: Poems for Strange Times (edited with Matthew

Sweeny, a very fine anthology of poems for all sorts of reasons, a great

addition to a book shelf).

Russell Jones

Monday, 1 September 2014

Poet Profiles, 1: Edwin Morgan

In a bid to share my poetry preferences and spread the good word about some fine poets, living and dead, I have decided to publish a fortnightly Poet Profile.

Have a gander...

Edwin Morgan

Have a gander...

Edwin Morgan

The background.

For anyone who knows me, this guy’s the obvious choice to

begin my poet profiles (my PhD was on his sci-fi poetry). Edwin Morgan

(1920-2010) was the Scots Makar until his death in 2010. He grew up in Glasgow,

serving abroad in WW2, returning to teach at Glasgow University. For all the ins,

outs and sideways of his life I’d recommend picking up “Beyond The Last Dragon:A Life of Edwin Morgan” by his great friend and biographer, James McGonigal.

Why this poet?

Morgan has to be one of the most exciting poets I’ve ever

read. His poetry is diverse, funny and profound. He’s written poems about the

Loch Ness Monster, Computer Christmas cards, space aliens, love, loss and

liberty. He’s written sonnets, sound poems, colour poems, sci-fi poems,

dialogue poems, concrete poems, one word poems, emergent poems... I could go

on. In short: check him out.

A poem extract.

Sssnnnwhuffffll?

Hnwhuffl hhnnwfl hnfl hfl?

Gdroblboblhobngbl gbl gl g g g g glbgl.

Drublhaflablhaflubhafgabhaflhafl fl fl –

gm grawwwww grf grawf awfgm graw gm.

Hovoplodok – doplodovok – plovodokot-doplodokosh?

A reading.

First, I have to express how much fun this poem is to read

aloud. You’d be missing out (and partly missing the point) if you just read it

in your head. Having taught this at secondary schools and universities, I know

how much of a kick people get out of hearing it spoken with gusto. Give it a

try, go on, now!

This is a sound poem, but the shape also adds to possible interpretations

we might make. At first the poem looks like nonsense, but there are hints of

intelligence in there. The monster asks questions, seeming to call out

dinosaur-esque names: “Hovoplodok – doplodovok – plovodokot-doplodokosh?”

Now Morgan has discussed what’s “happening” in the poem, but

to some degree that is irrelevant. The poem encourages you to make up your own

stories, to build a narrative from mere sound. Take that idea a step further and it starts to question the

nature of language: isn’t the way we engage with the world also linguistically

bound? And isn’t language simply an assortment of noises?

What’s the point then? Communication. Something ethereal is

communicated through listening to the poem, whether it’s merely humour or

something deeper. But the listener also begins to try to translate the poem. “What

is the monster saying? What’s happening?” They become an active participant,

decrypting the song and taking from it what they will. This was a major drive of Morgan’s work: communication is key, we need to work hard at understanding

each other.

This is a great example, I think, of how a poem can work

without the meaning of the words being the most important thing on the page. It

shows us how poetry can be effective and affective without “understanding” ever

being a part of the equation.

Go read...

Morgan has published SO many poems in books, magazines and

so on. If you’re new to his work I highly recommend his Collected Poems, which gives

a good sample of a wide range of his stuff. You can also listen to a few of his

poems on the Poetry Archive. If he grabs your fancy, visit the Scottish PoetryLibrary in Edinburgh, the home of The Edwin Morgan Archive.

Tuesday, 3 June 2014

Data Dump Award

Hello old friend. Have you been for a dump? I have. A data dump, of course. A ho ho ho. And a poo.

Data Dump is a regular newsletter about science fiction music, poetry and more, lovingly produced by Steve Sneyd. This is the ninth year that he's run a Data Dump Award for sci-fi poetry published in the UK and I'm happy to report that my poem, "After the Moons" won a gold star and took 1st place.

But here is also the information for those fine sci-fi poets who came in 2nd and 3rd. In some cases you can click their names to visit their blogs, sales pages and so on. Enjoy

1st

Russell Jones

"After the Moons"

from "Spaces of Their Own" (Stewed Rhubarb Press)

Joint 2nd

Andrew Darlington / JS MacLean

"Saturn Sigma Trojan Virus" / "Poetry is True Science Fiction"

Handshake 87 / Awen 82

Joint 3rd

Bryn Fortey / JC Hartley / Neil Wilgus

"Chaser and Chased" / "The Enigma Invasion" / "Yellow Dreams"

Bard 129 / Tiger Shark / Yellow Dreams

Russell Jones

Wednesday, 30 April 2014

Reviews reviews reviews

Writers are egotistical beasts, always on about me me me. Well I'm the worst of them all. Just look at this blog, it's entirely posts ranting on about moi. Disgusting.

So, here are some reviews (which I wrote, yes me, Russell Jones) of OTHER PEOPLE'S POETRY. You can even check out the poets' blogs or sales pages (in most cases), if you're that kind of person. Follow the links, comment, fornicate -

Click the poet's name to see their blog.

Click the book title to see my review.

“Separating

the Pieces: The

Cento, A Collection of Collage Poems

edited by Theresa Malphrus Welford”, The Istanbul Review, Issue 1

(2012)

“Evenlode:

Charles Bennett”, Elsewhere, (September 2013)

“This is Yarrow: Tara Bergin”, Elsewhere (October 2013)

“Muscovy:

Matthew Francis”, Elsewhere (December 2013)

“LeafGraffiti: Lucy Burnett”, Elsewhere (March 2014)

“Locustand Marlin: JL Williams” (March 2014)

“ProfessorHeger's Daughter: Chrissie Gittins”, Elsewhere (April 2014)

Russell Jones

Saturday, 26 April 2014

"Our Terraced Hum"

Much good news on the poetry front lately (now to sort out the rest of my meager existence!). Prole Books have decided to publish my sonnet sequence, "Our Terraced Hum".

It's part of an anthology called "Caboodle", which includes work from 5 other superstars of poetry:

Karina Vidler, Kate Garrett, Angela Croft, Gill McEvoy and Rafael Miguel Montes.

Due out in December, no doubt I'll update you again so your life can be filled with the joys of the publication process. I know you love it, you filthy thing you.

Russell Jones

Friday, 11 April 2014

Best Scottish Poems 2013

If, like me, you are suspicious of good fortune, then you may wish to throw a black cat under a ladder. My poem "The Ant Swap" from my sci-fi poetry pamphlet, "Spaces of Their Own" (Stewed Rhubarb Press) has been chosen as one of the twenty Best Scottish Poems of 2013!

The list was chosen by David Robinson, the books editor for The Scotsman, who had this to say about my poem:

"I love the mind-bending imagination of this poem, which zooms down to an ant-level view of the world before racing up into ‘the heat of stars, the prized melting flesh of my cosmos’, all somehow seen through a transfer of consciousness between the ant and the poet. I love, too, the image of ‘a tongue’s first flirt with noise’ employed as part of that wished-for transfer, and the signs that it has somehow been achieved, as the poet feels, instead of thought, a sense of the ‘heat of sugar’ that has lured the ant towards the ‘prized melting flesh of roadkill’, and the ant is able to imagine some sort of blissful human nirvana. And all in ten lines, too!"

Read the poem (or listen to my mad face reading it) on the Scottish Poetry Library Website.

Also included is work from:

Patricia Ace, Jean Atkin, John Burnside, Niall Campbell, Angela Cleland, Anna Crowe, Andrew Greig, Diane Hendry, Bill Herbert, Kathleen Jamie, Rob MacKenzie, Kona Macphee, Jim Mainland, J.O. Morgan, Thereza Munoz, Donald S. Murray, Robin Robertson, Ian Stephens and Jennifer Lynn Williams

READ THEM ALL HERE!

Russell Jones

Auld Reekie Readers

Far from stinking, Auld Reekie Readers is a group of readers and writers who meet up to share their work and listen to authors read.

As such I'll be talking about Edwin Morgan, sci-fi poetry, writing and editing, on Monday 14th April.

It's at the City Cafe in Edinburgh (EH1 1QR) and starts at 18:30.

Be there or be...somewhere else!

https://www.facebook.com/events/284725768357737/

Russell Jones

Monday, 31 March 2014

Writing...and monkeys

Writing...and monkeys

This is a post about writing, and that

mystical art of “process”. Essentially it's a bunch of blog posts

from various writers – known and unknown – about why they do what

they do, and how it is they go about doing it. It's not a book of

hints on “how to be a writer” or a set of tricks to get you

motivated, so far as I can tell, but a glimpse inside the private

lives of the freaks and geeks amongst us, those people who sit on

their lonesome and scribble down what the voices in their heads tell

them to say...

I received this calling to write a post

on “the writing process” from Pippa Goldschmidt, and as the

tradition dictates I shall now tell you a little about her:

Pippa is a professional astronomer,

which to me makes her incredibly cool before she's even opened her

mouth or put pen to paper. She is also the author of The Falling Sky, a novel which has received

great acclaim and which I ignorantly still need to read. But I do

know this: it's about a female astronomer whose discovery could

unravel current understandings of The Big Bang. She is also a fine

poet and I included her work in Where Rockets Burn Through:Contemporary Science Fiction Poems from the UK.

If you've an interest in science and fiction then she's a definite

go-to contemporary writer. Go, go check out her work and ramblings,

go now! You can check out her site here, which includes her own post about the way she goes about getting the good words down and chucking

the bad ones out.

And so

the nebula has been passed on to me. The task is to answer four

questions, so here we go...

Question

1: What am I working on?

Back

in January I was rowing in Ha Long Bay, in northern Vietnam. A guide

told me that on occasion, if you were lucky, monkeys could be seen climbing and chatting among the rocks. Now, I love monkeys. I love them a degree further

than is probably sane. I've visited a monkey temple in India, fed a

baby monkey in Thailand, I even have a t-shirt proclaiming my monkey

love. And yet no monkeys appeared on those rocks. Imagine, if you

can, my despair. I longed for those monkeys to voyage down, if only I

could call to them in a voice they could understand, they would

surely not deny me the pleasure of their company...

That's

the long route to saying this: I'm writing a novel about families who

can communicate with animals.

I'm

also still writing poetry and will shortly be editing my upcoming

collection The Green Dress Whose Girl is Sleeping

(due for publication with Freight Books in 2015) with editor Andrew Philip.

Question

2: How does my work differ from others of its genre?

I'm

perhaps most well known for my work in the sub-genre of Science

Fiction Poetry, having published two pamphlets of my own (“The Last Refuge” from Forest Publications in 2009, and “Spaces of Their Own” from Stewed Rhubarb Press in 2013) and edited a book of

contemporary sci-fi poems from the UK (“Where Rockets Burn Through”

from Penned in the Margins, 2013). The science fictional element

seems to have the ability to draw in new audiences, primarily fans of

SF, which I am very happy about because it gets non-poetry-readers a

bit more interested in poetry, as well as breaking apart some of the

snobbishness of poetry and genre.

So far

as the novel goes, it's a young adult book (of which there be many)

but aside from the story line I've been trying to challenge notions of

gender, race and class by inverting them. It's also a book about

politics and power, which are subjects I think we tend to –

incorrectly – shy away from when giving books to young people. It

will include lots of monkeys.

Question

3: Why do I write what I do?

This

is a question my mum would ask me. In terms of poetry, I write to

distill my thoughts and to see what language can do, how it can change

my perception. I think there's something almost scientific about

poetry, it's a process of discovery, of experimentation, of refining

and refracting, and re-examining the results. What comes out isn't

necessarily what went in, the conclusion isn't necessarily the aim.

And that's good because it bends the box and slaps you around the

face a bit.

My

novel feels more like an escape, a world I'd like to visit (although

probably not live in). It's a chance to explore my characters and see

who they become, as arsey and artsy as that sounds. Perhaps they're

imaginary friends; I want to help them out, to lead them down

uncertain paths and see what's on the other side.

In all

honesty there's a financial element to novel writing too. Poetry is a

labour of love, I know I'll never make my fortune from it. More

people are willing to pick up a novel and to pay for it.

Question

4: How does your writing process work?

I have

two rules when writing: don't do it when drunk, and don't do it when

overly emotional. I break them both.

A poem

starts as a line in my head, I hear it first like a piece of music from a broken

record that wants me to place the needle back on the groove. The poem

grows from that line, I don't know what it is when I start it and it's not always clear by the end. Sometimes I am interested in the poem as

an experiment. Hey what would happen if I wrote a bunch of

one word poems, or a sequence of sonnets about sexbots?

Sometimes it feels like more of an expulsion, to sweat something out

and jar it. A nice jar of sweat. I try not to force out or overwork a

poem, rather I just let them come as they will, sometimes a dozen in

a day, other times nothing for months. I almost always work on a

laptop: the appearance of the poem is very important to me and if I

need to scratch things out with pen and paper its messiness would

disturb me and throw me off the scent. Editing can take anywhere from

minutes to months. In 2008 I started a poem that is just 25 words

long, and I'm still not happy with it. That said, once I feel a poem

is finished I don't like to touch it after about 5 years. That feels

like I'm editing my old self, trying to pretend they didn't exist or

that somehow the person I am now is a “better” poet, with more

worthwhile things to say. And that seems very rude to Old-Me.

Writing

a novel feels more planned out. Probably because I use a

somewhat extensive plan. I know where things start, their potential

endings, but not necessarily the finer details in between. The

characters react and change, they think things over and respond. I

can't plan that part of things because I don't know the characters

well enough until they're faced with the dilemma, the romance, the

massive murderous bear with platinum claws that chases after them.

Redrafting prose is currently an enigma to me, although I imagine it

will be copious.

If

you've managed to get this far then well done! All that's left is to

introduce the next writer, Colin McGuire. Colin has published a pamphlet of poems about sleep, "Everybody Lie Down and No One Gets Hurt" with Red Squirrel Press, and is well known around the Scottish spoken word scene. He has reached the finals of the BBC Poetry Slam and runs a regular poetry night in Edinburgh, called Talking Heids. He can be followed on his blog, here! A full length collection of Colin's work is due out this year.

Peace

and monkeys be with you.

Tuesday, 25 March 2014

"The Last Refuge" e-book

Hear ye, hear ye, "The Last Refuge" (my 2009 pamphlet of sci-fi poems from Forest Publications) is now available on e-book.

It includes poems about A.I in supermarket barcode scanners, Android birthday parties, a poem from the perspective of a nuclear warhead and more...

It's only £0.77 and is a nice little taster to get you in the mood for "Spaces of Their Own" if you don't already own it.

Buy it here.

Russell Jones

Sci-fi Poetry Awards news

Yarr, ye scurvy Earth Lovers. Whilst I wes washin me space britches in the seas of Neptune I happened me across a few award nominations. Take yer hypershovel and dig at em, afore they leech into that thar parallel universe. Yarr.

Yeh "Spaces of Their Own" has been nominated for a few things, check em out:

* "Spaces of Their Own" nominated for the Elgin Award.

Find the other nominees here

* "After the Moons" nominated for the Rhysling Award.

Check out the other potentials here

* "After the Moons", "Re-entry" and "The Ant Swap" long listed for the 9th annual Data Dump Award.

Russell Jones

Wednesday, 12 March 2014

Listen to science fiction poems from Where Rockets Burn Through

The one-woman sci-fi poetry guru, Diane Severson Mori, has published an outstanding review of "Where Rockets Burn Through" and "Spaces of Their Own", on the Amazing Stories website.

It includes a big fat slice of sci-fi poetry recordings from a host of great contemporary poets, which I urge you to listen to RIGHT NOW.

Listen to poems by:

Jane Irina McKie

James McGonigal

Sarah Hesketh

Andy Jackson

Simon Barraclough

Jane Yolen

Dilys Rose

Aiko Harman

Ian McLachlan

Kirsten Irving

Kona MacPhee

Bill Herbert

Andrew James Wilson

Claire Askew

Sue Guiney

Ron Butlin

Pippa Goldschmidt

Russell Jones

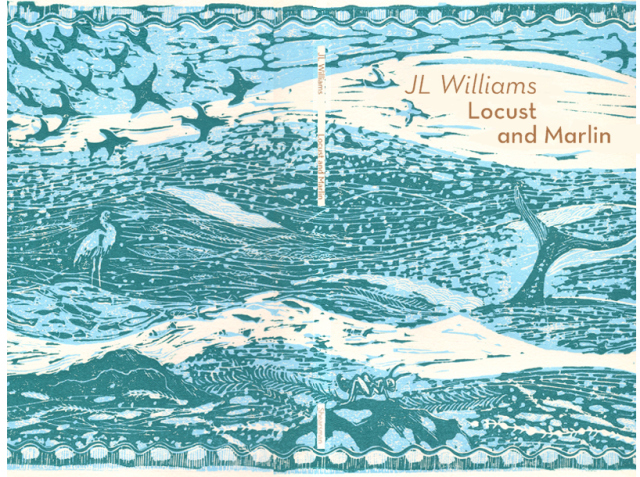

A poetry book review: Locust and Marlin by JL Williams

Locust and Marlin

JL Williams

Shearsman Books

Our position in the

world, and how we reflect on it, is one of the key concerns of this

book. This seemed apt to me as I sat in the sunny March of Holyrood

Park in Edinburgh, my dog panting at my side, Locust and Marlin

getting grubbied by my mud slathered hands. It was a fine setting for

reading this book (surrounded by volcanic hills, the hum of the city

in the background, people walking to work) in which nature, god and

our place in the universe are pondered. There is something quite

transformative about reading a collection of poems in a relevant

space, and the near-miracle of a Scottish sun made it all the

sweeter.

If Williams reads

this review then she may laugh at what I'm about to say, because when

I bought the book at the Scottish Poetry Library I obsessed over

this: the cover feels great. It's a peculiar thing to mention in a

book review but the front and back of Locust and Marlin has a

velvety finish that makes it pleasurable to hold. The cover image –

a sea blue menagerie with hidden images of insects, birds and fish –

also rings of the natural imagery and mythology to be found within

the poems. Shearsman have done a fine job in creating an artefact

worth holding, for sure.

But what of the

poems themselves? There's a refreshing brevity to Williams' work,

splashes of life and colour that aren't afraid to let themselves stop

ahead of schedule. These are glimpses, ruminations, reflections. They

avoid answers, and I admire that in a poem. A quiet confidence

permeates the collection, in which the poet taps us on the shoulder

to ask what we're doing. There are longer pieces too, some of

which were amongst my favourites as they begin to dig up the earth a

little more.

You could dip in

and out of this book and take something from each of the verses. The

opening poem, for example, “Heron”, is a short meditation on the

nature of the imagination, and a fine beginning to a collection that

requires us to fill in the gaps it leaves behind. I would like to

show the poem in full, but it's not the done thing, so here are the

first four lines (of seven):

Imagine a great

silence

whose wings touch

no branches.

Imagine a space

demarcated

by lack of sound.

Cleverly, this

heron is returned to in the final poem, “Revelation”, which is

only three lines long, ending: “the feeling of the fishes brushing

his legs”. The revelation is the acceptance of being, of nescience,

of its position in the world; a revelation which perhaps we share by

the end of the book. There's that biblical reference too, of course,

and this is a frequently visited home in the collection. The

narrators don't always quite know what to do with god, or the notion

of it. In “Like Phaeton (3)” for example, the “He” of the

poem remains ambiguous, its repetition almost mimicking laughter:

He.

He. He.

…

He does not speak

as others do.

Comparatively, in

“Son (3)” Williams writes:

God isn't here to

stake out dry tongues,

to lay claim to

scorched fields of hay.

This difference is

by no means a criticism of the approaches taken to such a demanding

topic, in fact a reduction of god, or an understanding of it, to

absolutes, would be to undermine the complexity of it. As a reader

with an innate aversion to religiousness in poetry, I was paranoid

that this frequent reference would irk or bore me, but that was

thankfully avoided. Williams considers the personal, theological and

psychological aspects of her core concepts to keep them refreshing.

Although they don't all hit the same notes, I was particularly

enamoured by the peculiar, sometimes even grotesque language in poems

like “Son”, in lines such as “The wind is a cow” and “I can

imagine how my lungs smell”. The anatomist in me likes that.

But this isn't to

say that the collection is without flaws. As the cover images imply,

there are a lot of seas, birds, fish and stones in this book. I'd say

the majority of the poems mention them at some point, and whilst

book-long tropes can be impressive, they did blur into one another at

times and I found myself thinking “oh bloody hell not another

stone”. This could have jarred the pleasurable experience of

reading the book as a whole, even though it did at times make chimes

and tinkles between the poems. And whilst the book asks questions, it

asks too many of them, and too overtly. It's full of rhetoric-isms,

and although this does lend itself to the nature of questioning our

spiritual and actual place in the world, the combined effect is to

dampen the concern of each (however well meant or interesting they

might be). The most successful poems present these ideas without

firing them – shotgun like – at us. These large concepts need to

be drawn out of the poem through the reader's interpretation, and in

poems such as “Blinding” (perhaps my favourite of them all) this

is achieved succinctly and powerfully. The closing lines read:

.........................................................women knead the

bread

water unveils

its secret

......................................................... hungry mouths

are fed

one to shine

one to see the

shining

The pleasure of

Locust and Marlin is most profoundly felt on reading it as a

whole. Its tone is inviting, gentle, reassuring in its subliminal

declaration that there are no real answers, and that we must each

find our place amongst the questions. As good poetry ought to, this

book made me leave that sunny park a little different to when I

arrived, and though I washed the mud from my hands when I got home

I've still got some of it under my nails.

Tuesday, 28 January 2014

Buying a Poster

A number of people have approached me about buying a copy of "1 in 5 teenagers with experiment with poetry" for their doors, fridges, trash cans and so on.

Unfortunately I do not own the images I used on the poster, as I only created it as a silly little thing to show my friends. It's now been shared many thousands of times.

In conclusion: sorry, I cannae print and sell you a poster. But feel free to take a good old gander at it on my blog, and to do as you see fit----

Peace

Russell Jones

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)