Locust and Marlin

JL Williams

Shearsman Books

Our position in the

world, and how we reflect on it, is one of the key concerns of this

book. This seemed apt to me as I sat in the sunny March of Holyrood

Park in Edinburgh, my dog panting at my side, Locust and Marlin

getting grubbied by my mud slathered hands. It was a fine setting for

reading this book (surrounded by volcanic hills, the hum of the city

in the background, people walking to work) in which nature, god and

our place in the universe are pondered. There is something quite

transformative about reading a collection of poems in a relevant

space, and the near-miracle of a Scottish sun made it all the

sweeter.

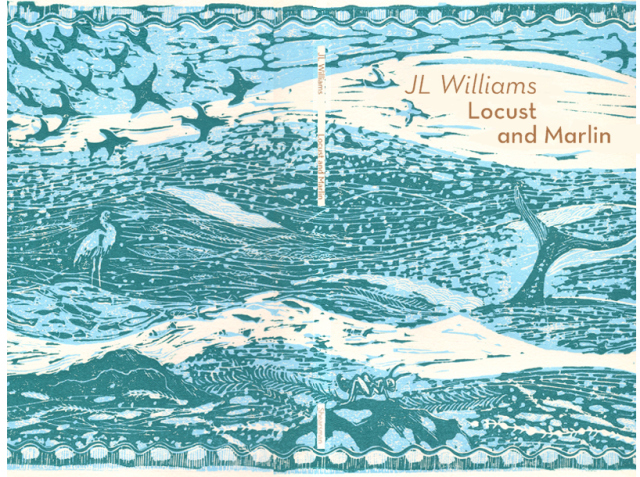

If Williams reads

this review then she may laugh at what I'm about to say, because when

I bought the book at the Scottish Poetry Library I obsessed over

this: the cover feels great. It's a peculiar thing to mention in a

book review but the front and back of Locust and Marlin has a

velvety finish that makes it pleasurable to hold. The cover image –

a sea blue menagerie with hidden images of insects, birds and fish –

also rings of the natural imagery and mythology to be found within

the poems. Shearsman have done a fine job in creating an artefact

worth holding, for sure.

But what of the

poems themselves? There's a refreshing brevity to Williams' work,

splashes of life and colour that aren't afraid to let themselves stop

ahead of schedule. These are glimpses, ruminations, reflections. They

avoid answers, and I admire that in a poem. A quiet confidence

permeates the collection, in which the poet taps us on the shoulder

to ask what we're doing. There are longer pieces too, some of

which were amongst my favourites as they begin to dig up the earth a

little more.

You could dip in

and out of this book and take something from each of the verses. The

opening poem, for example, “Heron”, is a short meditation on the

nature of the imagination, and a fine beginning to a collection that

requires us to fill in the gaps it leaves behind. I would like to

show the poem in full, but it's not the done thing, so here are the

first four lines (of seven):

Imagine a great

silence

whose wings touch

no branches.

Imagine a space

demarcated

by lack of sound.

Cleverly, this

heron is returned to in the final poem, “Revelation”, which is

only three lines long, ending: “the feeling of the fishes brushing

his legs”. The revelation is the acceptance of being, of nescience,

of its position in the world; a revelation which perhaps we share by

the end of the book. There's that biblical reference too, of course,

and this is a frequently visited home in the collection. The

narrators don't always quite know what to do with god, or the notion

of it. In “Like Phaeton (3)” for example, the “He” of the

poem remains ambiguous, its repetition almost mimicking laughter:

He.

He. He.

…

He does not speak

as others do.

Comparatively, in

“Son (3)” Williams writes:

God isn't here to

stake out dry tongues,

to lay claim to

scorched fields of hay.

This difference is

by no means a criticism of the approaches taken to such a demanding

topic, in fact a reduction of god, or an understanding of it, to

absolutes, would be to undermine the complexity of it. As a reader

with an innate aversion to religiousness in poetry, I was paranoid

that this frequent reference would irk or bore me, but that was

thankfully avoided. Williams considers the personal, theological and

psychological aspects of her core concepts to keep them refreshing.

Although they don't all hit the same notes, I was particularly

enamoured by the peculiar, sometimes even grotesque language in poems

like “Son”, in lines such as “The wind is a cow” and “I can

imagine how my lungs smell”. The anatomist in me likes that.

But this isn't to

say that the collection is without flaws. As the cover images imply,

there are a lot of seas, birds, fish and stones in this book. I'd say

the majority of the poems mention them at some point, and whilst

book-long tropes can be impressive, they did blur into one another at

times and I found myself thinking “oh bloody hell not another

stone”. This could have jarred the pleasurable experience of

reading the book as a whole, even though it did at times make chimes

and tinkles between the poems. And whilst the book asks questions, it

asks too many of them, and too overtly. It's full of rhetoric-isms,

and although this does lend itself to the nature of questioning our

spiritual and actual place in the world, the combined effect is to

dampen the concern of each (however well meant or interesting they

might be). The most successful poems present these ideas without

firing them – shotgun like – at us. These large concepts need to

be drawn out of the poem through the reader's interpretation, and in

poems such as “Blinding” (perhaps my favourite of them all) this

is achieved succinctly and powerfully. The closing lines read:

.........................................................women knead the

bread

water unveils

its secret

......................................................... hungry mouths

are fed

one to shine

one to see the

shining

The pleasure of

Locust and Marlin is most profoundly felt on reading it as a

whole. Its tone is inviting, gentle, reassuring in its subliminal

declaration that there are no real answers, and that we must each

find our place amongst the questions. As good poetry ought to, this

book made me leave that sunny park a little different to when I

arrived, and though I washed the mud from my hands when I got home

I've still got some of it under my nails.

No comments:

Post a Comment